Projects

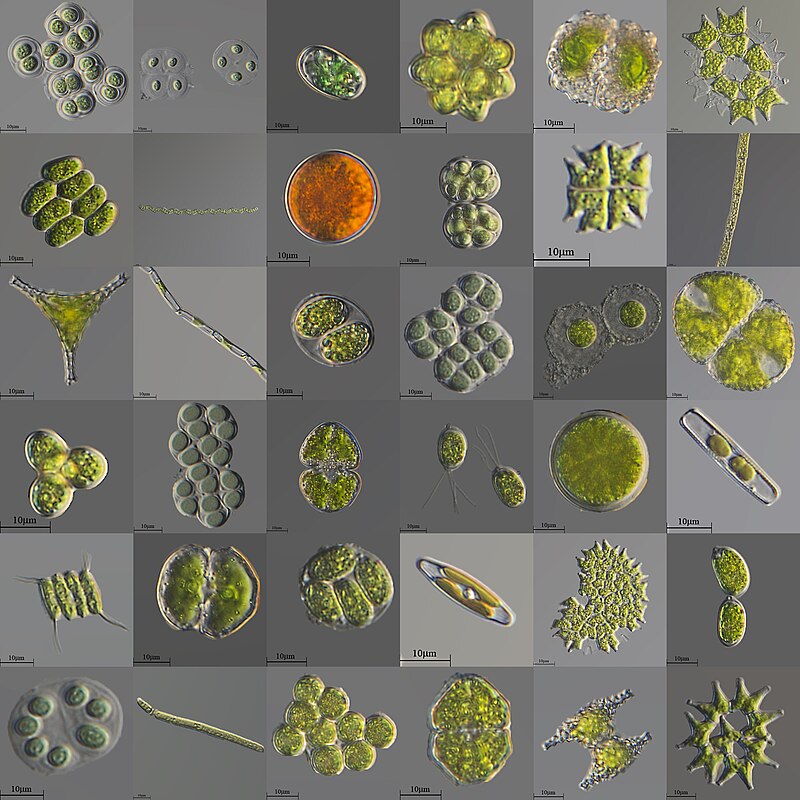

Lake plankton ecology

Most research on plankton ecology has focused on the oceans. However, it is imperative that we improve our understanding of freshwater plankton ecology for a number of reasons:

1) Freshwater biodiversity is even more threatened than marine or terrestrial biodiversity. To figure out how to protect freshwater species we first have to understand their ecology.

2) Phytoplankton form the base of the lake food web, and zooplankton form a crucial link from microbes and algae to fish. Therefore, plankton play a starring role in the important functions performed by lakes, from primary production and carbon cycling to fish production.

3) Plankton are responsive to environmental conditions, including temperature, pollution, water clarity, and water chemistry in general, making them useful as environmental indicators.

…among other reasons…

I am working with the international Zooplankton as Indicators Group to study the relationships between lake zooplankton and their environment, including their relationship to phytoplankton. Since there haven’t been any global freshwater plankton monitoring efforts, we are using a compilation of datasets contributed by researchers around the world. Learn more about the project here.

Higher order interactions

Most community ecology theory is based on two-species interaction models. However, real communities almost always have more than two species, and they are rife with emergent interactions that pairwise relationships fail to predict. Furthermore, we don’t yet understand how these emergent interactions (AKA higher order interactions) might change under different environmental conditions. I am approaching this question using experiments with several duckweed species.

Along the way, I realized that methods for this type of experiment are not well developed. To aid in processing duckweed growth data, I am collaborating with computer scientists to develop an AI computer vision model to identify duckweed species and measure their growth in photos. Also, measuring higher order interactions often requires very large experiments and therefore raises the question of how to design such experiments efficiently; yet, there is little if any published statistical guidance. Therefore, I am running computer simulations of experiments and re-analyzing experimental data to develop a guide for designing efficient higher order interaction experiments.

Trophic Cascades

I study indirect effects of predators on primary producers using miniature pond experiments and theoretical models. Besides “classic” trophic cascades, I investigate the effects of predator diversity and intraguild predation strength (essentially, how much predators eat each other) on both the central tendency and the stability of basal ecosystem properties like phytoplankton biomass.

Relevant publications

Rakowski, C. J., M. A. Leibold, and C. E. Farrior. 2025. Strengthening intraguild predation increases the temporal variability of biomass across all trophic levels in model food webs. bioRxiv <https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.25.661600>.

Rakowski, C. J.,and M. A. Leibold. 2022. Beyond the fish-Daphnia paradigm: testing the potential for pygmy backswimmers (Neoplea striola) to cause trophic cascades in subtropical ponds. PeerJ 10:e14094 <https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14094>.

Rakowski, C. J., C. E. Farrior, S. R. Manning, and M. A. Leibold. 2021. Predator complementarity dampens variability of phytoplankton biomass in a diversity-stability trophic cascade. Ecology e03534 <doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3534>.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning

I use experiments and theory to study the ecosystem-level consequences of biodiversity change. Within this realm I am especially interested in ecosystem stability and incorporating food web interactions.

Relevant publications

Wolf, A. A., S. K. Ortiz, and C. J. Rakowski. 2022. Ecosystems: an overview. Chapter 3 in M. Loreau, F. Isbell, and A. Hector, editors. The ecological and societal consequences of biodiversity loss. ISTE, London, UK. Link.

Rakowski, C. J., C. E. Farrior, S. R. Manning, and M. A. Leibold. 2021. Predator complementarity dampens variability of phytoplankton biomass in a diversity-stability trophic cascade. Ecology e03534 <doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3534>.

Rakowski, C., and B. J. Cardinale. 2016. Herbivores control effects of algal species richness on community biomass and stability in a laboratory microcosm experiment. Oikos 125(11):1627-1635 <https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03105>.

Applications to algae cultivation

I tested methods for biological zooplankton control using fish in algae cultivation ponds. The goal is to improve the reliability of phytoplankton cultivation for environmental technologies by reducing the impacts of zooplankton in a budget- and environmentally-friendly manner.

Relevant publications

Rakowski, C. J., M. A. Leibold, and S. R. Manning. 2024. Sunfish as zooplankton control agents to improve yields of wastewater-cultivated algae. Journal of Applied Phycology <https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-024-03281-3>.